Age: 13+ Middle School, High School Half or Full Credit

Turn music history from a daunting subject to an entertaining part of your homeschool with the engaging performances and accessible writing of this course.

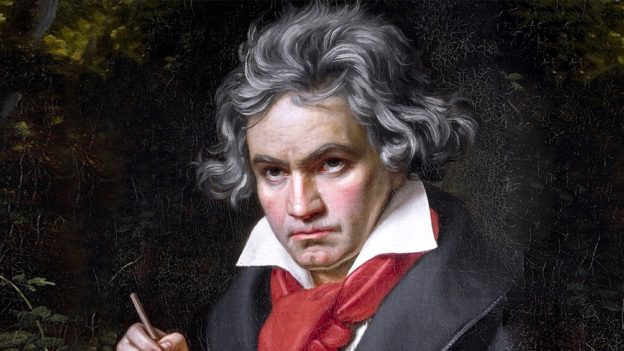

Take an exciting tour through the history of Western music with this engaging and accessible course. This course combines composer biographies, musical eras, and live performances with curated playlists to help students understand and enjoy classical music on a deeper level.

Students will:

- Learn the chronological development of Western music from the Middle Ages through the early 20th century.

- Explore influential composers and musical styles across major historical periods.

- Watch high-quality video performances and listen to curated audio playlists.

- Complete quizzes and research projects to reinforce understanding and critical listening skills.

- Use the course as a fine arts elective or as enrichment for music students wanting historical context.

This flexible course can be taken for a half or full high school credit and serves as a fun and thorough foundation in music history and appreciation.

- In-depth written materials on each musical period and composer of note through the beginning of the twentieth century

- High-quality performances of the music

- Quizzes and research projects

- Audio and video playlists and recommended recordings

- Additional resources for going deeper into many composers’ works

Our Bronze Membership provides online access to this and 30+ additional courses, PDF course books, audio stories, and a customer support group.

Our Silver Membership adds Family Access (5 logins) and facilitation for courses through our Groups. Course facilitation provides:

- Direct encouragement from instructors.

- Additional links of interest that support learning in the course.

- Live Zoom meetings with facilitators to discuss lecture material and assignments.

Our Gold Membership adds grading, homeschool support, and discounts on live courses.

You can learn more (or upgrade your current plan) on our Membership Page. Our support team of homeschool moms can also answer your questions. Visit our support page to contact them.

All courses can be accessed on desktop, mobile, and through our Compass Classroom App (iOS & Google).

Learn more about The Story of Great Music at compassclassroom.com.

Course Content

Introduction

About Instructor

Thomas Purifoy, Jr.

A creative filmmaker who develops unique learning resources intended to advance the Kingdom of God. Thomas helped develop a classical-based curriculum, and taught philosophy, Old Testament, film and history at the American School of Lyon, France. Thomas studied English at Vanderbilt University and is a former Officer in the US Navy. He currently oversees Compass Classroom and Compass Cinema.

6 Courses