Mozart in Vienna

In the early spring of 1781, Mozart was in Munich performing his opera Idomeneo. It proved an undeniable success. While there, however, Mozart received a peremptory order to join the Archbishop in Vienna.

He had to tear himself away from his success and obey, although there was no clear reason for the order. After arriving in Vienna, the Archbishop treated him insolently. He refused to allow Mozart to play in public or at the houses of nobility. He intentionally slighted him when others admired him, and showed a complete disregard for Mozart’s abilities. Mozart asked to be discharged. The Archbishop responded with abuse, and after much argument, the situation ended in Mozart’s dismissal.

It is difficult to understand how this young man of twenty-five years could have any difficulty making his way in Vienna, the most artistic society of the time. He had a brilliant record of musical successes in many countries, he had attracted the favourable notice of the Emperor, and he had been badly treated by a man whom the Emperor hated.

Yet the system of patronage was so strong that a musician of the highest order who tried to live unattached to the service of a nobleman found it difficult to obtain a satisfactory living. This was Mozart’s situation.

In spite of these setbacks, Mozart never stopped composing. In 1781, he produced many marvelous works, with the following sonata for two pianos as one of the masterpieces of the year.

Listen to the first movement of the Sonata for Two Pianos, K. 488 (6 min)

Listen to 6:10. The first movement is an ‘allegro con sprito’ (‘quickly, with spirit’). This very spirited performance features the talented brothers Lucas & Arthur Jussen. The delight of Hadyn’s music is on full display in their dazzling performance.

Haydn and Mozart Meet

During the winter of 1784, following his discharge, Mozart finally met Haydn. From that point forward, their lives began to interact musically.

Haydn had come to Vienna on leave from Esterhàzy for the performance of some of his quartets. The two men likely met at the house of a nobleman who had engaged Mozart to play. Haydn was now 52; as we have seen, he had fought through the difficulties of youth and achieved an easy and profitable way of life.

Mozart, after a youth in which his genius had blossomed freely, was now feeling the hardships of the world. The genial sympathy of the older man was balm to Mozart, and the more strenuous nature of the younger one was stimulating to Haydn.

It may even have struck Haydn that in the quietness of his own life he had missed some of the finer and more sensitive qualities which he found in Mozart’s music. Certainly he was humble enough to learn from one who in terms of age might have been his own son. Mozart was enthusiastic enough to hail with joy the master of the string quartet.

Over the next three years, Mozart wrote six new string quartets and dedicated them to Haydn. They are now known as Mozart’s ‘Haydn’ quartets, and include some of his most extraordinary writing. He prefaced this letter to his gift:

To my dear friend Haydn,

A father who had resolved to send his children out into the great world took it to be his duty to confide them to the protection and guidance of a very celebrated Man, especially when the latter by good fortune was at the same time his best Friend. Here they are then, O great Man and dearest Friend, these six children of mine. They are, it is true, the fruit of a long and laborious endeavor, yet the hope inspired in me by several Friends that it may be at least partly compensated encourages me, and I flatter myself that this offspring will serve to afford me solace one day. You, yourself, dearest friend, told me of your satisfaction with them during your last Visit to this Capital. It is this indulgence above all which urges me to commend them to you and encourages me to hope that they will not seem to you altogether unworthy of your favour. May it therefore please you to receive them kindly and to be their Father, Guide and Friend! From this moment I resign to you all my rights in them, begging you however to look indulgently upon the defects which the partiality of a Father’s eye may have concealed from me, and in spite of them to continue in your generous Friendship for him who so greatly values it, in expectation of which I am, with all of my Heart, my dearest Friend, your most Sincere Friend,

W. A. Mozart

Listen to the finale of Mozart’s String Quartet No. 14, K. 387 (5 min)

Played here by the Engegard Quartet during a recording session. It is a delightfully fun performance.

Mozart and Haydn enjoyed an ideal friendship which affected their music. Neither could be overly influenced by the other, for each was too firmly established in his own ideals. But both could advance some distance along the lines of the other’s approach.

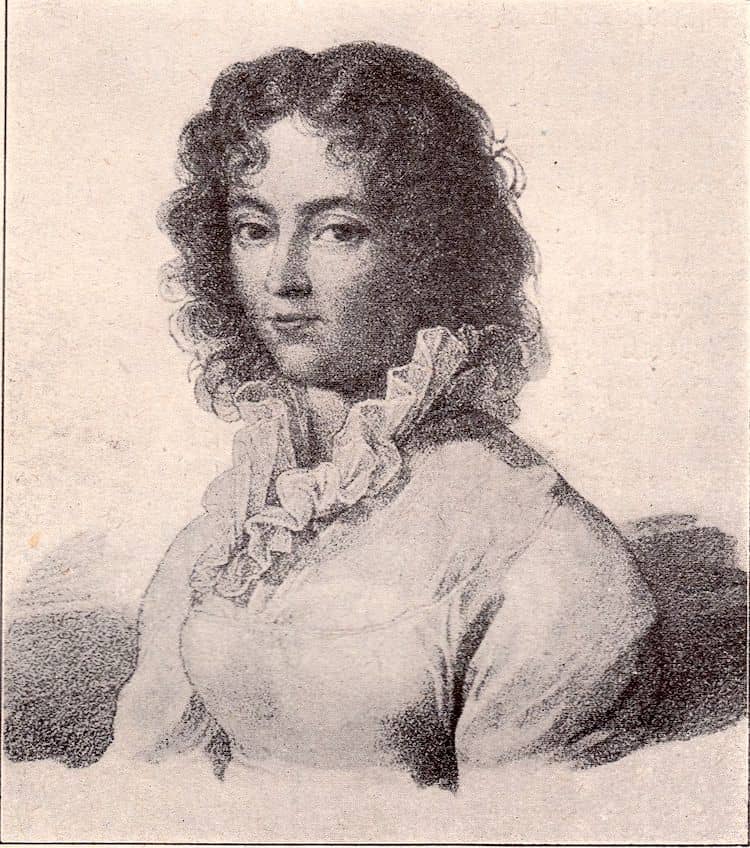

Constanze Mozart

In 1785, another beneficial event helped to stimulate Mozart, although it added to his material cares. He married Constanze Weber, whom he had met years before in Mannheim. She was now living in Vienna. Mozart’s marriage was another point of contrast with Haydn’s. Mozart and his young wife were genuinely attached, sharing their joys and troubles with deep affection. Haydn, sadly, experienced an unhappy marriage.

Nevertheless, Mozart and Constanze always seemed to be but a few steps from poverty. This was partly because of the difficulties of his employment, and partly because neither was wise at managing money.

They lived chiefly in Vienna. While there, Mozart came up with a unique solution to his financial woes. He started a series of ‘subscription’ concerts for which he wrote and performed all the music. He sold them to the aristocratic and wealthy Viennese public. It was for these concerts that he composed many of his concertos for piano and orchestra, which make up one of the most important branches of his compositions.

Mozart himself would be both conductor and soloist at these events, in which he wrote and performed the music with small ensembles.

Watch the opening to Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20, K. 466 (5 min)

Play approximately 5 minutes (unless you’d like to watch more). This particular performance features Swedish composer-pianist Roland Pöntinen as conductor and performer. It was chosen to demonstrate what one of Mozart’s performances might have felt like. Note that his concerto No. 20 is a darker piece; it opens with the orchestra stating the theme, then the piano picks it up after a few minutes.

In 1785, Leopold Mozart paid a visit to his son and daughter-in-law. He was disappointed at his son’s lack of worldly success, but found comfort in meeting Haydn at their house. Hadyn turned to Leopold and said, “I declare before God that your son is the greatest composer that I know either personally or by reputation.”

The Marriage of Figaro

In 1786, Lorenzo da Ponte, a famous writer of ‘librettos’ (opera stories and dialogue), asked leave of the Emperor to adapt Beaumarchais’s comedy, The Marriage of Figaro for Mozart. The comedy was a satire on the habits of court life which was frowned upon by aristocrats across Europe.

The Emperor was at first unwilling to give his consent, but eventually did so. In da Ponte’s hands the play became an irresponsible piece of light-hearted fooling.

Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) was produced in Vienna with enormous success. This was strong encouragement for Mozart, whose opportunities for producing operas in the capital had been few. But this success in Vienna was short-lived compared to the wonderful reception Figaro achieved in Prague the same year.

The entire city of Prague rejoiced in Mozart with an intensity Vienna had never displayed. It was the capital of an exceedingly musical people, whose taste was less overloaded by the stream of foreign artists than that of the Austrian aristocracy. The people of Prague immediately embraced the sparkling vivacity of Mozart’s comedy.

Watch the first scene of The Marriage of Figaro (8 min)

Watch until 8:00. The opera begins with an overture, then turns to a duet between Susanna and Figaro about their upcoming wedding (which includes English subtitles). This performance is conducted by Bernard Haitink. (By the way, the characters are introduced during the overture, so don’t be surprised when they show up on the screen.)

The delight did not stop with Figaro. Mozart was a hero, and his playing at concerts and improvisation at the piano on themes from Figaro kept enthusiasm at a high pitch. His Symphony No. 38 in D which he wrote for these concerts, and which is still known as the ‘Prague Symphony’, shows in its happy quality how he responded to the general positivity.

Mozart returned to Vienna since he could not afford to lose touch with its wider musical life. But Prague was not done with him. Another opera was commissioned, and in the autumn of 1787 his masterpiece Don Giovanni was produced there with equally great acclamation. A powerful and intense opera, it is a dark comedy that examines the downfall of the adulterous Don Juan.

The story of how the overture to Don Giovanni was composed the night before the first performance, and how Mozart’s wife talked to him and gave him a punch to keep him awake is often repeated to show how rapidly he could compose.

But such rapidity was common among eighteenth century composers. It was partly due to certain musical forms generally being accepted, and partly due to Mozart almost always having clear musical ideas in his head.

The story, however, is an interesting example of a curious habit of Mozart’s. He would constantly go to work and write the necessary pieces of a new opera to make the whole scheme clear to himself. He then left it, only returning in time to hurry and finish the remaining details before the work was heard.

Listen to the Overture from Don Giovanni (6 min)

Conducted by Ricardo Muti in the Vienna Opera House. This clip is taken from the full performance, so it includes credits and titles at first.

The End of Mozart’s Career

Don Giovanni was the herald of the most important period in Mozart’s career. Mozart had achieved his ambition in opera; he now had to put the crown upon his work as a writer of symphonies. His three most famous symphonies—numbers 39, 40, and 41—were all written in this same year, 1788.

In spite of all these achievements, his financial position remained unsatisfactory. The small post of Court composer given by the Emperor was only sufficient to keep him attached to the Viennese court lest he should be tempted to go somewhere else.

He had, in fact, serious thoughts of trying his fortune in England (of which he had many happy memories from his youth). The following year, he accepted an invitation to visit Berlin; but when King Frederick William II made him a generous offer, he could not bring himself to accept it at the price of banishment from Vienna.

For us, the most interesting experience Mozart had on this journey links him with J. S. Bach. He stopped at Leipzig on the way to Berlin and made the acquaintance of the cantor, a pupil of J. S. Bach. Mozart played the organ at Bach’s famous Thomaskirche (St. Thomas Church).

Doles (the cantor) was greatly struck by his playing, and he made his choir sing for Mozart’s benefit. They sang J. S. Bach’s motet ‘Singet dem Herrn’ (Sing to the Lord), which like practically all Bach’s choral music, was then unknown to musicians outside Leipzig. Mozart’s enthusiasm was aroused, and he exclaimed: “Here is something from which one may still learn!” He spread out the parts of Bach’s motets before him (no scores were to be had) and became absorbed in studying them.

The only tangible result of the visit to Berlin was a commission to write some string quartets. After he returned to Vienna, the rest of Mozart’s career consisted of strenuous efforts in composition(particularly opera), difficulties with money, and his concern with the illness of his wife. His own health soon suffered, and he had a complete breakdown. He died December 5, 1791 and was buried anonymously in a pauper’s grave.

These last years include the light opera Cosi fan tutte and the comic opera Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute). The latter was written for Schikaneder, the manager of a poor German-speaking theatre in the suburbs of Vienna, and continues to be one of his three most popular operas today with Figaro and Don Giovannni.

We cannot leave Mozart’s life, however, without a mention of the Requiem Mass which occupied his last weeks of work and haunted him in his illness. He had been commissioned to write it by a man who adopted an air of mystery, refusing to tell him from whom the commission came. The reason for the mystery seems to have been an attempt to secure Mozart’s work and present it as someone else’s.

Nevertheless Mozart, distracted and quite ill, looked upon the work as a supernatural warning of his own death. He often spoke of the Requiem as being composed for himself. Yet try as he might, he could not complete it before dying. Thankfully, according to his custom, he had written enough of it to reveal the main design to his pupil Süssmayer, who eventually finished it for posterity.

Listen to the opening Introit of Mozart’s Requiem K. 626 (7 min)

Start at the beginning and listen through 6:40. This is an incredible historic performance from the 1960’s by the famous Mozart conductor Karl Bohm with the Vienna Philharmonic.

Mozart Explains His Approach to Music

Mozart wrote: “It is a mistake to think that the practice of my art has become easy to me. I assure you no one has given so much care to the study of composition as I. There is scarcely a famous master in music whose works I have not frequently and diligently studied.

“When I am at peace with myself, and in good spirits—for instance, on a journey, in a carriage, or after a good meal, or while taking awalk, or at night when I can’t sleep—then thoughts flow into me most easily and at their best. Where they come from and how—that I cannot say; nor can I do anything about it. I retain the ideas that please in my mind, and hum them—at least so I am told. If I hold fast to one, that I think is suitable, others, more and more, come to me, like the ingredients for a pate, from counterpoint, from the sound of the various instruments, and so forth. That warms my soul, that is if I am not disturbed, and keeps on broadening those ideas and making them clearer and brighter until the whole thing is fully completed in my mind.

“I’d be willing to work forever and forever if I were permitted to write only such music as I want to write and can write—which I myself think good.”