Mozart’s last six symphonies are his most popular symphonies. They are extraordinary masterpieces of the height of the Viennese Classical tradition, each revealing new perfections and variations of the sonata form. They include:

- Symphony No. 35 in D, ‘Haffner’ (named after a wealthy Salzburg family)

- Symphony No. 36 in C, ‘Linz’ (named after the Austrian town)

- Symphony No. 38 in D, ‘Prague’ (named after the Czech town)

- Symphony No. 39 in E flat

- Symphony No. 40 in G minor

- Symphony No. 41 in C, ‘Jupiter’ (named after the first movement)

We will take a minute to look at four of them in detail: 35, 38, 39, and 40. (No. 39 is included on ‘Watch a Full Work’ and No. 41 at the end of ‘Mozart’s Music’)

Symphony No. 35 in D ‘Haffner’

The ‘Haffner’ symphony, written in 1782, has an arrestingly brilliant opening phrase in its first movement. What seems to be a display of virtuosity, however, is turned to extraordinarily fine musical uses later.

Through all the development of the first movement this phrase dominates the score. While one instrument is playing the long notes of its first two bars another is beating out the emphatic rhythm of its fourth.

The second movement andante contrasts with the strenuousness of the first movement by the delicacy of its themes. These themes are ornamented with passages in rapid notes which, like similar ornaments in Mozart’s piano sonatas, seem to spring to his mind as memories of the graceful coloratura of the opera.

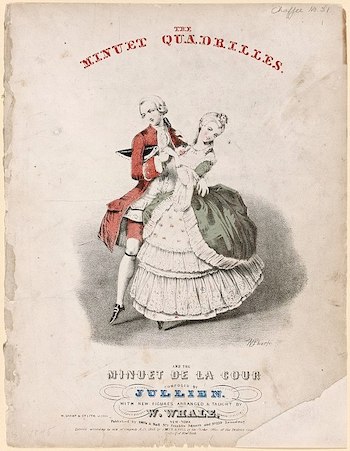

In the third movement we have a very charming minuet, not developed elaborately like that of the G major quartet, but made of a few phrases of melody in which the instruments give strong contrasts of color. The oboes and bassoons who lead the trio give a delightful relief from the more glowing tones of the strings in the minuet itself.

The finale shows Mozart in his most vivacious vein. There is something peculiarly flavorful about its principal theme played ‘piano‘ (softly) by the strings in unison, followed suddenly by an outburst of merriment. Each time that Mozart comes back to this tune he has a new way of gliding into it, so that it continually surprises us with a fresh feeling of playful mystery.

Listen to Mozart’s Symphony No. 35 in D major K. 385, ‘Haffner’ (18 min)

A spirited performance by the Orchestra of the Academy of Santa Cecilia with Sir Antonio Pappano conducting.

Timings: 1 Allegro con spirito. 0:00 | 2 Andante. 5:35 | 3 Menuetto. 10:05 | 4 Presto. 13:05

Symphony No. 38 in D ‘Prague‘

The ‘Prague’ Symphony does not begin straight away with the allegro. Instead, it opens with a slow movement that forms an introduction to the symphony which in turn leads up to the first allegro. This was a common practice with both Haydn and Mozart, and has been followed by later composers of symphonies.

Very often it seems to be merely a survival of the idea of the French overture, which was adopted freely by composers of all nations. The idea was that an important work ought to have an imposing opening to arrest attention; but the greatest composers often used it to better purpose.

The slow introduction to the Prague symphony does open in a formal way; its first bars reiterate the keynote D with triplet figures running up from the dominant A. This is one of Mozart’s common figures of speech (compare the beginning of the Jupiter symphony).

After this opening phrase, he marches up the notes of the key and reaches a chord of F sharp major, which resolves to B minor. This striking harmonic idea gives him his chief text for the introduction.

Notice it is repeated softly on another pair of chords and yet again by the woodwinds (flutes, oboes, and bassoons) passing into E minor, from which point the violins begin a new melody. Bold modulations of key occur in the introduction (D minor, B flat, G minor) as though the composer wished to range widely before he settles down to the main business of his scheme. There are also strong contrasts of tone; at one moment the whole orchestra is massed upon a big chord; at another, delicate figures for the violins or separate wind instruments are heard individually.

The variety of Mozart’s orchestration can be well studied here and in the allegro which follows. See, for instance, how many details go to make up the interest of the chief allegro theme; there are the violins playing a throbbing syncopated figure, the basses pressing up beneath them, also syncopated, though in a broader style, then the flutes and oboes in octaves rippling down the scale followed by a mournful melody for the oboe alone. The development, too, is quite entrancing in the way the separate instruments dovetail into one another and in the game they make with that downward scale passage which the flutes and oboes first introduced.

The slow movement gives a good example of Mozart’s fondness for chromatic decoration of his melody, for after two bars of very simple outline the violins begin the process, and when the flutes take up the tune they carry the chromatic variation still further. It is altogether a most tenderly thought out movement beautifully colored by the instruments.

In the finale, the violins begin a race which in turn is taken up by all the members of the orchestra. Though it has none of the more serious elements of a fugue(such as we found in the finale of the quartet in G), the chasing of one instrument by another and the imitations and suggestions of ‘stretto’ show how thoroughly at home Mozart was in a contrapuntal style.

The whole symphony strikes one as intensely happy, so that it stands as a truly fitting record of one of the brightest moments in Mozart’s career, which contained too few bright moments, when for the time he felt all the flush of success and the joy of a friendly enthusiasm around him.

Listen to Mozart’s Symphony No. 38 KV 504, ‘Prague’ (34 min)

Performed here by the Vienna Philharmonic under the direction of famous Czech conductor Rafael Kubelik.

Timing: 1. Adagio–Allegro – 0:00 | 2. Andante – 10:39 | 3. Finale Presto – 19:29

Symphony No. 39 in E flat

The reason the world has agreed to place the three symphonic masterpieces of 1788 (Sym. 39, 40, & 41) in a place by themselves seems to be that each is so extraordinarily unique, inventive, and perfect that they are monuments to Western art.

We may agree that nothing more brilliant in its own way could be conceived than the Prague symphony, but we had seen Mozart working in its direction in the Paris and Haffner symphonies. But each one of the last three symphonies sheds an entirely new light on Mozart’s character.

The Symphony No. 39 in E flat has a breadth and graciousness of outline which it would be difficult to match in any work before Beethoven. Mozart uses a larger orchestra, and clarinets take the place of oboes. The score contains one flute, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, drums, and strings.

The symphony in E flat begins with an adagio introduction, as the Prague symphony does. But instead of a unison rhythm, we have a majestic one in full harmony. Moreover, this rhythm is the basis of the whole introduction.

When the strings vary it with rapid downward scales it is reiterated softly on the woodwinds. When the flute adds a new interest in a passage of broken quavers, the same rhythm is heard throbbing on a single low note played by violas, violoncellos, and basses.

It is partly veiled by a long roll on the drums. It asserts itself again strongly with the violins, horns, trumpets, and drum. These stronger members of the orchestra combine to lead towards a climax of tone. The whole orchestra breaks off with a strong discord, after which a soft phrase of melody, curiously scored for flute, violin, and bassoon, leads to the allegro.

The introduction shows well how far Mozart’s orchestration had proceeded. One feels certain that he must have thought of the tune and the instruments playing it together. The violin begins and is immediately echoed by the horns; it adds a second phrase, to which bassoons respond. Then we have the tune more richly sounded by violoncellos and basses, against which clarinets and flutes echo its ideas while the higher strings decorate it with new harmony.

It is exceedingly simple, yet this one passage is sufficient to show why Mozart was a great master of orchestration. It is because every note adds an indispensable touch to the color.

The fascinating slow second movement is in A flat. Though trumpets and drums are omitted, it is as full of variety and color as the first movement. The full orchestra reasserts itself in the vigorous third movement (a minuet). One cannot pass by this movement without specially pointing to the trio. For here more than anywhere else we see what new material the clarinet brought to the orchestra. The melody of the trio is played by the first clarinet accompanied by the second one in an arpeggio figure. If two oboes played this, they would have a very buzzy sound. The more liquid tones of the clarinets ripple instead of buzzing.

As regards the extraordinary finale, we must only glance at the first and last bars in order to realize the originality of the ending. In many symphonies of the eighteenth century the ending could become forced. Composers seemed to find it necessary to go on repeating perfect cadences and striking big chords.

But here the first phrase of his principal tune is the last phrase of the symphony. He seems to have caught a gleam from Haydn’s humor in ending with delightful abruptness, and (though not quite so daring) this ending is to some extent in the same spirit as that of J. S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2. The Symphony No. 39 is pure beauty and delight.

Listen to Mozart’s Symphony No. 39 (27 min)

Timings: 1 Adagio – Allegro. 0:00 | 2 Andante con moto. 9:47 | 3 Menuetto & Trio. Allegretto 19:02 | 4 Finale. Allegro 21:18

Symphony No. 40 in G minor

The G minor symphony presents a new pinnacle of Mozart’s symphonic genius. There is no attempt to make a stately impression at the outset; the first melody of the allegro slips shyly into existence, its little pairs of quavers gathering confidence for a wider sweep like a young bird fluttering its wings before flying.

As in some of his chamber music, the form of the tune gives rise to all sorts of developments later; yet though many things happen, the first fresh beauty is never brushed off. The whole is extraordinarily supple and buoyant from the first tune to the soaring arpeggio which gives the theme power to the finale. The G minor symphony is lyrical while the ‘Jupiter’ is dramatic, and that is why it is so intensely lovable.

We will make no analysis of it here. If the examples and comparisons in this lesson have been understood they will suggest general lines which may act as guides in the study of this and other symphonies by Mozart and Haydn.

There is no more delightful musical adventure than taking a symphony which one has heard once or twice and exploring all of it, finding what is unexpected in the developments of rhythm and harmony, the changes of key, and the new colors given by the different uses of the instruments. To map out the ground, set up signposts, and provide a chart would be to spoil the sport of the true adventurer.

It is possible this is Mozart’s most beloved symphony. It is truly one of the greatest works of all time.

Listen to Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor (39 min)

Performed by the Chamber Orchestra of Europe conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt.

Timings: 1 Molto Allegro. 0:00 | 2 Andante. 8:37 | 3 Menuetto & Trio. Allegretto 22:41 | 4 Allegro assai. 27:28