If one forbids a child to practice an instrument or to take an interest in music, will he become a great musician?

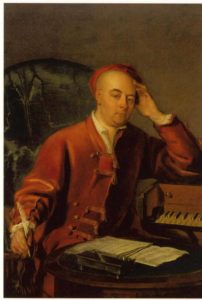

The story of George Frederick Handel would seem to suggest it. Handel’s father was a barber at Halle in the German state of Saxony. He was a practical man who turned his energies toward earning a comfortable living. As a result, he had an intense dislike of any art and especially music—he saw it as a waste of time.

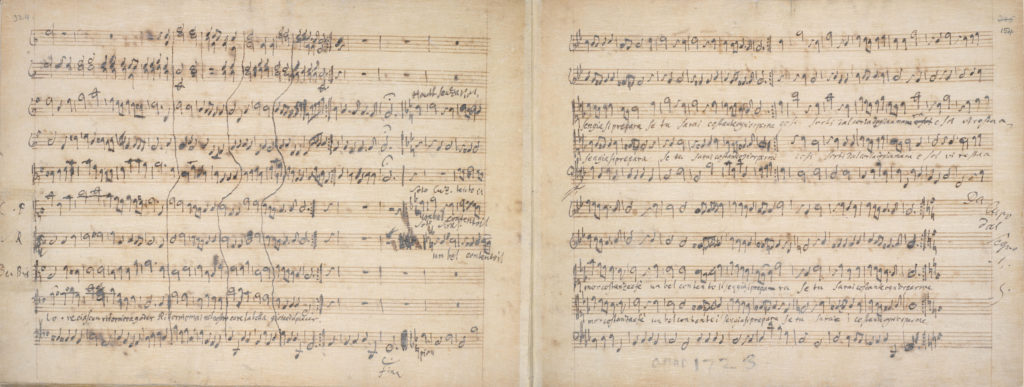

His son George Frederick was born in 1685. His father made up his mind he should become a lawyer. One day the boy discovered an old clavichord hidden in an attic. He had been forbidden to try to play any instrument, but every night when he was supposed to be in bed he would creep up and play. Eventually he was discovered, and his father was very angry.

First Music Lessons

When George Frederick was seven years old, he was taken to the court at Weissenfels when his father went there on a visit as surgeon. While the father was busy, the boy made friends with the court musicians who allowed him to play the organ in the chapel.

The Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels heard him and was so struck by his abilities that he persuaded the father to allow the boy to have good music lessons. Such interest from a prince was really an order, so whatever the surgeon himself felt about it, he had to agree that his son should have lessons.

Handel took them from Zachau, an organist in Halle. Handel studied with him for three years and learned to play the organ, harpsichord, violin, and oboe, as well as studying counterpoint and harmony.

At the age of twelve, Handel became assistant organist at the cathedral church of Halle. Five years later he was appointed organist. One year after this he stopped his studies of law, which all this time had gone on side-by-side with his musical work.

He moved to Hamburg and secured a post as violinist in the orchestra at the opera house. The conductor of the orchestra played the harpsichord and directed his players away from that instrument. A lucky chance came when the conductor was absent gave Handel the opportunity to show how skillfully he could do such work.

From that time he became the leading harpsichordist in the orchestra. His experience there with opera helped much in the writing of those operas which formed the greater part of his work for many years to come.

Handel was certainly a man of spirit and would allow no one to interfere with his work as he thought it should be. A colleague called Mattheson had an opera produced and, as was usual then, wished to direct part of the performance from the harpsichord.

Handel refused to give up his place, and as the quarrel could not be allowed to interrupt the performance it ended afterwards in a duel outside the theatre. Mattheson was the better swordsman, but fortunately for music he broke his weapon on a button of Handel’s waistcoat.

During the Hamburg period, Handel had his first operas produced. He had now learned all he could at this theatre and his thoughts turned more and more to Italy, the home of opera at this time. He decided he must travel there to learn all he could.

Listen to ‘Oboe Concerto No. 3’ in G Minor (4 min)

This is one of Handel’s first published pieces from 1705, performed here on original instruments by Musica Gloria with Nele Vertommen playing oboe. You can listen to the first two movements (or the entire piece).

Timings: 0:00 Grave | 2:14 Allegro | 4:03 Sarabande: Largo | 6:12 Allegro

Handel in Italy

He arrived in Italy in 1707 and visited Florence and Rome. He met Alessandro Scarlatti, father of Domenico as well as other operatic writers. The Italian composers above all others excelled in writing for the voice, perhaps because their singers had the most naturally beautiful and flexible voices.

Their influence on Handel was very great and helped make him one of the finest composers of vocal music that ever lived. In his music, the lovely Italian style was grafted onto the solidity and depth of German musical thought.

In Venice, Handel met the noted harpsichord player Domenico Scarlatti. Obviously the German’s fame had gone before him, for it was said that when Scarlatti heard someone playing brilliantly on the harpsichord he exclaimed: “It is either the Saxon or the devil.” The two entered into friendly rivalry and each had a great respect for the other’s gifts.

After three years in Italy, Handel was appointed kapellmeister (chapel-master, i.e. conductor of the musicians who played in the chapel and provided the other music of the court) to the Elector of Hanover. When he took the post, he arranged that he should be allowed time for a visit to England which had been suggested when he was in Italy.

This visit lasted for six months. The only important work produced was the opera “Rinaldo,” written in fourteen days.

It is recorded that the whole play was gorgeously put upon the stage and that everything that scenery and stage mechanism could do to make it effective was done, even to the flight of hundreds of birds on the stage in the scene of the enchanted garden. Whether because of these trivial details or because the English audience had never heard songs of such sustained power, beauty, and variety, the result was a complete success.

The following aria from Rinaldo is one of the most moving that Handel wrote. It is a good introduction to his incredible talent.

Listen to ‘Lascia ch’io pianga’ (Let me weep) from Handel’s Rinaldo (4 min)

Performed by Kirsten Blaise (soprano) with Voices of Music. Click on captions for English subtitles. The full translation is included in the drop down menu.

Handel in England

The musical conditions of London must have made a good impression on Handel, for two years later he came again. This time he stayed for good.

He came on leave from the Elector’s court but soon overstayed his time. His operas were produced, and he wrote a Te Deum to celebrate the Peace of Utrecht. Queen Anne was so pleased with this that she granted him a yearly pension of £200.

On the death of the Queen, the composer found himself in an awkward position. His master the Elector was naturally annoyed with his kapellmeister who had deserted his court duties to please himself by producing operas and making music in London. But now the Elector of Hanover was proclaimed the new King George I of England. Handel was no longer in favor at the English court.

After a brief visit to Hanover with the King, Handel took charge of the music in the household of the Duke of Chandos. This very wealthy nobleman had a palace in Whitehall and a country estate at Canons Park near Edgware. Handel lived for two years at Canons Park composing operas, anthems (called the Chandos anthems), chamber music, harpsichord music, and orchestral music for the Duke.

During his stay with the Duke of Chandos, Handel composed several vocal pieces for royal events. These pieces, along with certain movements from his oratorios, display Handel’s unparalleled ability to make music with a truly royal quality.

One of the best examples of Handel’s royal music is the bright and lively “Arrival of the Queen of Sheba.” This instrumental piece opens Act 3 of one of Handel’s last oratorios, Solomon. This last oratorio is often said to be a tribute to the grandeur of England under the Georges, with the wise and majestic King Solomon representing King George II.

Listen to the “Arrival of the Queen of Sheba” from Solomon HWV 67 (3 min)

Handel’s Career in Opera

At the end of three years, Handel was the chief figure in London’s then busy operatic world. A society was formed called the “Royal Academy of Music” to produce operas at the King’s Theatre. Handel became one of its directors. He went to Dresden to find singers and engaged some of the finest artists in Europe.

In all, Handel wrote thirty-nine operas for performance in London. Their subjects included “Julius Caesar,” “Tamerlane,” “Orlando,” and similar classic and legendary tales. The style of the solos was infinitely varied, though Handel had a trick of borrowing from his own works, and sometimes from those of other people.

No other composer considered his singers as Handel did. They were given opportunities to display the good qualities of their voices. A flexible voice had light and ornamental passages to show it off. A rich voice whose beauty lay in sustained notes had phrases of slow, full melody. When a voice was incapable of holding interest by itself, Handel wrote a richly woven accompaniment. A singer whose voice was of outstanding merit and vitality would often be left almost entirely without instrumental support.

Handel was generally on good terms with his singers, but he insisted on having his own way. When he was defied he flew into a rage. One singer, Cuzzoni, complained that an aria Handel had written for her was too difficult to be sung at all. Whereupon Handel “let loose his bear,” as his biographer Burney says, and threatened to throw her out of the window if she did not sing it. She did sing it and scored a great success.

For a short time, Handel persuaded the two great rivals Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni to appear in the same opera. He carefully gave them equal importance, but, alas, the truce only lasted for a short time.

The two singers quarrelled and even fought on the stage; the fashionable ladies of the audience at first thought it a great joke, and then took sides and started rowdy rival factions. At last no performance could proceed without the interruptions of hurrahs and hisses, regardless of the merits of the performers. This rivalry was the beginning of the failure of Italian opera in London.

The constant hard work for so many years and the financial worries affected Handel’s health. In 1737 he had to go to Aix la Chapelle, France to find a cure for paralysis. He came back in time to compose a funeral ode for the Queen.

The expenses of the Royal Academy of Music at last proved so great that it could not continue. Handel suffered great financial losses, but not to be beaten by rival factions, he went into management on his own. The taste for Italian opera was gone. The typically English “Beggar’s Opera” had just been produced and was drawing large crowds. For the second time, Handel went into bankruptcy. He undertook to pay off all his debts, and in time he was able to do this.

Handel’s Oratorios

At the age of fifty-two, Handel began the composition of the type of work for which he is most greatly revered. As we discussed in the Italian Baroque, an oratorio is a kind of sacred opera performed without any action. The parts are sung, but not acted.

His experience in writing opera showed Handel that very dramatic musical effects could be obtained with large choruses. However, the conventions of Italian opera and the difficulties of dealing with large numbers on the stage did not allow for this development in opera. Handel therefore turned his attention to Biblical stories in which all the drama should be expressed by music and not by action.

The English people have given greater appreciation and understanding of choral music than any other nation. Handel had lived long enough amongst them to know the kind of music which appealed to them. The new works therefore greatly increased his already great fame.

In 1726 he became a naturalized Englishman, and in 1738 public appreciation was shown by the erection of a statue in Ranelagh Gardens.

He produced “Saul” and a setting of Milton’s “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso” with the addition of an “Il Moderate” in 1738. In 1741 he started on a journey to Dublin. He had to wait in Chester for his boat, and Dr. Burney, a lifelong admirer of Handel who was then a schoolboy, spent all his spare time watching the great man.

Burney told an amusing story of the member of a church choir who was summoned to sing some of the arias in Handel’s new work for him. The man failed miserably. Handel was furious, and raged, “You scoundrel, did you not tell me that you could sing at sight?” “Yes, sir, and so I can, but not at first sight,” answered the man.

Later on, Burney met Handel frequently and took every opportunity of playing under his conductorship. He describes him as “a blunt and peremptory disciplinarian on these occasions, but had a humour and wit in delivering his instructions, and even in chiding and finding fault, that was peculiar to himself, and extremely diverting to all but those on whom his lash was laid.”

The visit to Dublin was extremely successful and its glowing climax was the production of a new oratorio, “Messiah.” The story of its composition is rather remarkable. Handel’s friend Charles Jennings had given him a new libretto based on the life of Christ. Handel himself was depressed with his state of affairs in life. Although he was a man with faith in God, he had fallen on difficult times financially and publicly.

He worked nonstop on the new oratorio, never leaving his house for over three weeks. A friend who checked in on him found him sobbing from the intense spiritual feelings. But he did not stop. In a mere 25 days he finished 260 pages of new music. At one point, in talking about writing such heavenly music, he quoted the apostle Paul saying, “Whether I was in the body or out of my body when I wrote it, I know not.”

Sir Newman Flower, one of Handel’s biographers, observed that, “considering the immensity of the work, and the short time involved, it will remain, perhaps forever, the greatest feat in the whole history of music composition.”

The people of Dublin were tremendously enthusiastic; there had never been an oratorio like this before. It was simply extraordinary.

Londoners seem to have been more restrained when it was subsequently performed in their city. Nevertheless, the effect of the “Hallelujah Chorus” was so electrifying that involuntarily the King sprang to his feet. Of course, the rest of the audience had to stand too, and it has been the custom ever since to stand for that chorus.

Listen to “Hallelujah” Chorus from Messiah (4 min)

This stirring performance is by the Kings College Cambridge Choir. The text is taken from the book of Revelation.

Several performances of the oratorio were given, and annually a superb one in aid of the Foundling Hospital in Bloomsbury, a charity in which Handel was interested. The work became more and more admired until it won its position as the greatest oratorio of all time and that on which Handel’s fame universally rests. Every year the composer gave a performance for the benefit of the Foundling Hospital, to which at his death he left a substantial legacy.

Oratorios followed each other just as the operas had done. Unfortunately the singers were not so good as the opera singers had been and the country was disturbed by the Stuart rebellion. The “Occasional Oratorio” was a result of this rebellion, and “Judas Maccabeus” was written to celebrate the Battle of Culloden. It contained another of his most famous choruses.

Handel’s Final Years

Handel’s personal faith in Jesus Christ continued to grow in the closing years of his life. His close friend Sir John Hawkins said that he “throughout his life manifested a deep sense of religion. In conversation he would frequently declare the pleasure he felt in setting the Scriptures to music, and how contemplating the many sublime passages in the Psalms had contributed to his edification.”

Besides operas and oratorios Handel had composed many harpsichord works and some organ concertos which he used to play in the intervals between the acts of his operas. At this time he wrote his finest works for string orchestra, two sets of 12 Concerti Grossi.

In 1751 he composed the oratorio “Jephtha” and found his eyesight failing. He underwent three operations for cataracts. At first it was hoped that these had proved successful, but at last the papers announced that Handel was completely blind.

He still went about and took an interest in musical events. From time to time the old trouble of paralysis returned, and the great man’s powers were waning rapidly. After attending a performance of “Messiah” in 1759 he was taken ill and died on 14 April, aged eighty-four. He was buried with much honour in Westminster Abbey.

England can be proud that she was the chosen home of one of the world’s greatest musicians, and that the English love of choral music inspired Handel to write some of the world’s masterpieces. If he had never written anything else his name would be revered for “Messiah.”

His oratorios, keyboard works, and instrumental music are frequently played, and except for the improvement in orchestral instruments, they are heard in the same way, and with as much joy, as in the time that Handel wrote them.

Listen to Handel’s Concerto Grosso Op. 6, No. 7 (12 min)

This is a splendid performance by players from the German WDR Symphony Orchestra. At times moving, at times joyful, it fully captures the spirit of Handel’s music. It opens with one of the loveliest largos Handel wrote for his Concerti Grossi.

Timing: 1. Largo – 0:00 | 2. Allegro – 1:09 | 3. Largo – 3:50 | 4. Andante – 7:00 | 5. Hornpipe – 11:07