Corelli’s Sonatas

Archangelo Corelli (1653-1713) was the first great violinist of history. He devoted his whole life to playing his instrument and composing music for it and other stringed instruments.

Corelli’s works are of two kinds:

- Sonatas for one or two violins with a bass part to be played both by a violoncello and a harpsichord (the harpsichord player adding chords to fit with the other parts according to his discretion)

- Concertos, in which three solo players (two violins and a violoncello) play together accompanied by a band of stringed instruments, violins, violas, and violoncellos.

Some of his sonatas were played at the meetings of the Accademia, of which both Scarlatti and Corelli became members in 1706. In the same year, a young German composer named George Frederick Handel visited Rome and attended some of the meetings. He listened to Corelli’s work and learned much from it. We will come back to him later.

The sonatas generally contain four movements: slow, quick, slow, quick. Each movement is divided into two sections.

The first section gives out a melody which modulates into some other key at the cadence. The second, beginning in that key, returns to the one from which the first started, using some fragments of the melody given out by the first and adding others.

A melody is a series of single notes in order perceived as a unity. Think of “Twinkle, twinkle little star” – that is a famous melody by Mozart. His good friend Joseph Haydn once said, “it is the melody which is the charm of music, and it is that which is most difficult to produce. The invention of a fine melody is a work of genius.” (We will learn more about both Mozart and Haydn in future lessons.)

Watch a short documentary on the Baroque Violin (2 min)

A violinist with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment explains the differences between a Baroque and a modern violin.

We will look particularly at one of Corelli’s sonatas—Opus 5, No. 3 in C major. It begins with an ‘adagio’ (slow movement) and then ends with an ‘allegro’ (fast movement).

You can tell at once that it is violin music. The way the opening slowly emerges holding the notes for a long time, or how the allegro jumps about in so sprightly a way – it would be hard even to play such a tune on the piano. But it is perfectly written for the violin and shows how well Corelli understood the character of his instrument.

The movements are very short. One of the things composers had not yet learned to do was to carry on the tunes and sustain the interest through long movements. But you will find that each of the two movements has a strong, rhythmic character.

Listen to Violin Sonata Op. 5, No. 3 by Corelli (1 min)

Although you are welcome to listen to the entire piece, you can get a sense of what his violin sonata sounds like by listening to the first minute.

Corelli’s Concertos

There is more variety of form in Corelli’s concertos. When many instruments play together, it is possible to get more contrast between the solos and the full band. As a result, the same phrases of melody could be repeated by different instruments.

Corelli’s writing is less distinctly instrumental in his concertos. Sometimes there are passages which remind one strongly of choral music. An example is the famous opening of his eighth concerto, which looks and even sounds like a piece of the old style church music.

Such passages, however, are the exception in Corelli. His music marks a turning-point in the life of instrumental music, since he gave it stronger character than it had possessed before.

Corelli did further service to his art by founding a great school of violinists who, as we shall see, carried on his principles in playing and composing for their instrument through the next century. Meanwhile, his music was a model for his contemporaries, and it remains a delight for us today because of its lovely melody and its purity of design.

Listen to the ‘Christmas Concerto Op. 6, No. 8’ by Corelli (4 min):

Start at the beginning and listen through 3:50. You are welcome to listen to more, of course.

Domenico Scarlatti and the Harpsichord

Domenico Scarlatti was born in 1685. This is a year to be remembered by all musicians, since in it George Frederick Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach were also born.

Dominico devoted himself to the harpsichord and wrote a great number of lovely little pieces which he called sonatas. But his use of the name, which Corelli also used, is an example of the puzzling fact that different things in music are often called by the same name.

Unlike Corelli, Domenico’s sonatas are generally in one movement. They are not made out of dance tunes, ‘sarabandes,’ or ‘giges’, but are rather more like toccatas (that is to say pieces written for the display of the player’s skill).

They are almost all quick movements, requiring the utmost skill and precision. They are full of brilliant gaiety and high spirits which was quite new to the music of the time.

People who were used to the solemn beauty of church music or to the pomp of operatic overtures or arias must have been taken by surprise when young Scarlatti poured out these little pieces full of glitter and humor.

Today, we can see that these sonatas were far in advance of anything which had been written for the harpsichord. Their only fault is that they are so much in the same vein of feeling.

This is a good moment to look a bit closer at the keyboard instrument known as a harpsichord. You’ve already heard it play a few times, but it is rather different than a modern piano in that it plucks the strings instead of striking them with a hammer.

Watch a short documentary on the harpsichord (3 min)

Scarlatti loved the harpsichord and each of his compositions for it is perfectly worked out.

He modulates from one key to another with even more ease than his father. His musical ideas are more consistently carried out, and the ideas themselves are always fresh and frank.

Some modern pianists delight to play his sonatas on the piano at the present day (just as violinists delight in playing the sonatas of Corelli). A certain thoroughness seems to belong to both Scarlattis, father and son. They worked in narrow limits, but within those limits their work was nearly perfect.

You may see a “K.#” listed on each piece of Scarlatti’s music. This is an ordering system created by the world renown harpsichord player Ralph Kirkpatrick…hence the K.

Listen to Jean Rondeau play Scarlatti’s Sonata K. 175 on harpsichord (2 min)

Listen to the first few minutes to get a sense of how technically demanding these pieces are to play.

Sometimes, the same piece of music can be played on different instruments to bring out different aspects of the composition. Here is a famous piece by Scarlatti played on a modern piano, then a modern guitar.

Listen to Vladimir Horowitz play ‘Scarlatti Sonata K.380’ on piano (4 min):

Vladimir Horowitz is is one of the most beloved pianists in the 20th century; this is taken from his famous concert in Moscow in 1987.

Listen to ‘Scarlatti Sonata K. 380’ on guitar (2 min):

Listen to the first few minutes of this recording to compare the differences in sound. Since a harpischord and a guitar both are instruments that pluck strings, they at times sound very similar.

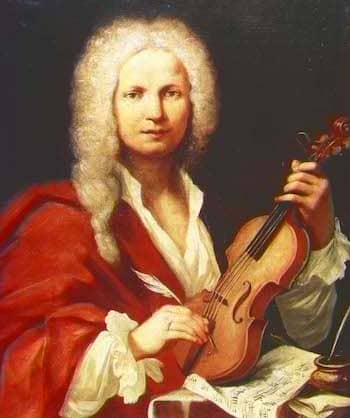

Antonio Vivaldi

Antonio Vivaldi is the most famous of the Italian baroque composers. His music is still played around the world today and its popularity never wanes.

He was born in Venice in 1678. After completing his church studies, he was ordained a priest in 1703. During this period, he was a musician, too, and achieved recognition both as composer and as violinist.

In 1709, he became music master of an orphan’s hospital for girls. During that time he composed music for its various groups as well as directed its concerts. Between 1725 and 1735 he traveled throughout Europe as virtuoso and composer of operas.

Vivaldi was the master of the concerto form. It is through his solo concertos for violin and particularly his concerti grossi (large concertos) for orchestra that he is remembered and honored today (although he wrote countless concertos for all sorts of instruments). Johann Sebastian Bach admired Vivaldi’s works so profoundly that he arranged sixteen of the violin concertos for piano, four for organ, and one for four pianos and string quartet.

With Corelli, Vivaldi stands as one of the forefathers of the modern concerto form. In his voluminous writings in this field — for violin, for piano, and for orchestra — he brought the form to altogether new stages of technical development in which the structure was amplified and filled with artistic and

poetic expressions not found even in Corelli.

Vivaldi represents the tendency of Italian art toward harmonic form, such as we saw in Italian opera. Simple clarity of design and superficial effectiveness were the principal virtues.

Vivaldi was essentially a violinist. At times—especially in slow movements an expressive melody inspired him—he wrote some of the most beautiful music ever written.

Vivaldi’s Concertos

Two major sets of concerti grossi by Vivaldi are of particular importance. The first of these, Opus 3, is entitled L’Estro armonico (Harmonic Inspiration) and comprises twelve works.

Note that the Latin word opus is used regularly in music to designate an order of a composer’s works. Unfortunately, it does not always signify the chronological order in which the works were written, sometimes referring to publication date, and sometimes to some other order. But it is a useful way to tell works apart.

One of these works, the 11th in D minor, is one of the greatest of Vivaldi’s works in this vein. The first Allegro (Italian for ‘quickly’) opens with a robust subject which is tossed about among the various branches of the strings and emerges finally in a powerful climax.

The Intermezzo (Italian for ‘interval’) slow movement is one of the most sublime and moving pages of music to be found before Bach. It is a pastoral song of soaring and eloquent beauty. The final Allegro comes in with a powerful sweep to bring the concerto to a blazing close.

Listen to Vivaldi’s Op. 3, No. 11 from L’Estro armonico (8 min)

Vivaldi wrote a seemingly endless stream of concertos for almost every baroque instrument, including the lute. His Concerto for Lute in D minor is often played today with a modern classical guitar. The middle movement is a largo (Italian for “very slow”) and exquisitely beautiful. Here is a performance by the world-renowned classical guitarist, John Williams.

Listen to the Largo from Vivaldi’s Lute Concerto in D Minor (4 min)

Although you are welcome to listen to the entire piece, advance to 3:45 to hear the Largo.

The Four Seasons

The second major set of concerti Grossi is the Op. 8. This was called by the composer II Cimento dell’ Arrnonia e dell’ Inventioni (The Trial of Harmony and Invention). The first quartet of works in this opus is subtitled, in turn, Le Quatro Staggioni (or The Four Seasons). This last work represents some of the most amazing program writing in music.

Vivaldi actually attached to each of these concerti a sonnet of his own creation which was intended to indicate the program of his music.

In the first concerto, Spring, we hear the singing of birds, the bubbling of fountains, and the pastoral pipings of shepherds. In Summer, the song of the cuckoo is prominent, and with it the cooings of turtledoves. The program here actually describes a sleeping shepherd disturbed by flies! Autumn gives a picture of Bacchus and a hunting scene. Winter recreates the cold (we hear the chattering of teeth in the music!) and describes a perilous walk on ice.

The modern Italian conductor, Bernardino Molinari, adapted these four “seasonal” concertos for modern orchestras, and in this version these works have been widely heard.

In the next step, you’ll be able to watch an entire performance of The Four Seasons.