So far, the German states have had little to add to the story of music. This is not because the Germans are unmusical. Rather, there were a number of causes that kept them from taking the lead in the artistic developments in which Italy, France, and England were all prominent.

Geographical and political conditions combined to keep Germany back. In the 16th century, it was a vast tract of country cut into innumerable states which were much isolated from one another. As a result, it did not have the centers of culture such as Italy possessed in Rome, Florence, and Venice, or France in Paris. Although a great deal of music was composed in Germany from the time of the Meistersingers and Minnesingers onward, the rest of the world heard little of their efforts.

Added to that, the religious disturbances in Germany checked the growth of church music at a time when it was at its best elsewhere. Martin Luther published his famous protest against the teachings of Rome in 1517, and those parts of Germany where Protestant doctrines prevailed had no use for complex and mystical styles of choral music.

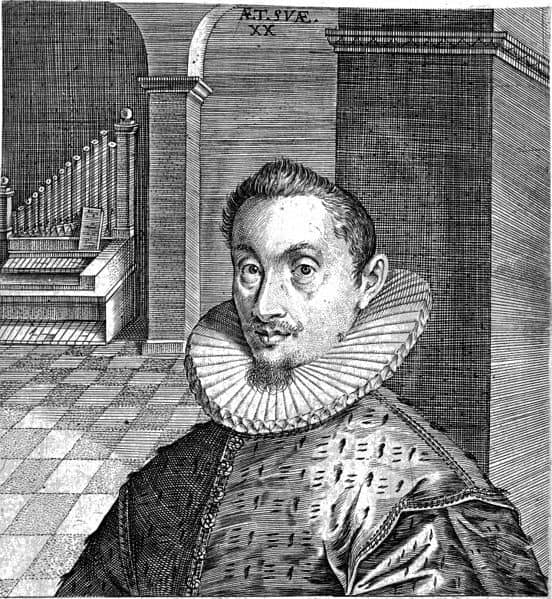

Church Music: Leo Hassler

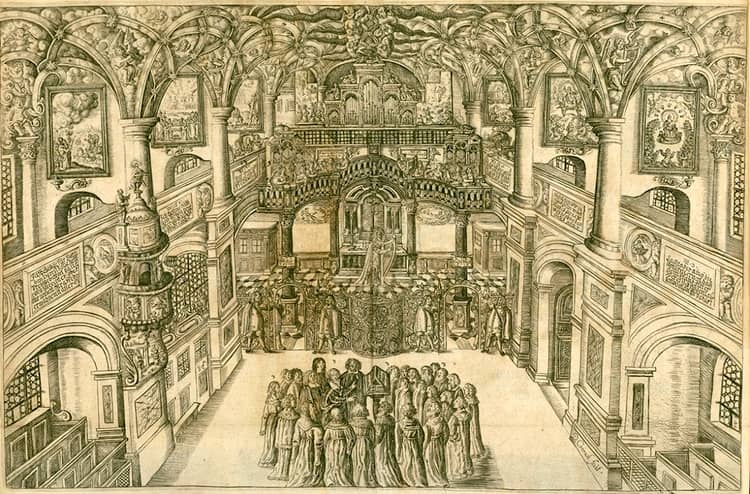

Instead, the German people learned to write church music of quite another kind. They composed or adapted tunes so that ordinary people could sing to the accompaniment of the organ.

The Reformation in Germany was much more drastic than in England. Although English Protestants persecuted Catholics, and Catholics burned Protestants when they got the chance, eventually the country settled down to a compromise where there were no national rules or principles as to how the musical side of worship should be conducted.

This was not the case in the Lutheran churches. Instead, the principle was that the music, like the words, must be such that the people could understand and join in. This was so insisted upon that almost all existing music, except some of the old plain-song hymn tunes, became unusable.

We must go back, therefore, and trace the advance of music in Germany from an earlier date than the latter part of the seventeenth century. Composers, headed by Luther and his friend Johann Walther, began to write simple hymn tunes called by the Germans chorales. They also adapted old church tunes and folksongs for the purpose.

Some are known in English-speaking churches, such as the one called Luther’s hymn and translated as ‘Great God, what do I see and hear’. Another is the lovely tune sung to ‘O sacred Head, sore wounded’, the work of Leo Hassler.

Listen to ‘O sacred Head, sore wounded’ (3 min)

These tunes became very dear to German Protestants. Their musicians would play them on the harpsichord and write variations upon them; or they would add ornamental passages and counterpoints to the simple tunes. It was from these sources that sprang both the vocal church music and the instrumental music of Germany as it appeared at the end of the seventeenth century in the works of J. S. Bach.

Hassler himself was a musician of the older school. Most of his work, such as the mass for eight voices, was written in the polyphonic style like that of Palestrina. But the beautiful chorale mentioned above, though it was intended to be a secular song, became one of the very foundations of Protestant church music.

Heinrich Schütz

A still more striking figure in early German music is that of Heinrich Schütz. He was born in Saxony in 1585 and lived to a great age.

He was one of the first musicians who realized it was possible to combine the best characteristics of the various kinds of music leaping into existence at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

The fact that his father was a man of some social position meant Heinrich was given the benefit of a university education. He also had the advantage of a certain amount of foreign travel. This enabled him to take a broader view of music as a whole than the ordinary German musician.

Schütz was able to study and admire both the choral music of Palestrina and the new dramatic ideals of Peri, Monteverdi, and others. He saw that it should be possible to use the vivid expression of the new style without sacrificing all the grandeur and dignity of the old.

In 1614, he was appointed ‘Kapellmeister’ (i.e., chief court musician) to the Elector of Saxony, whose court resided at Dresden. He was required to reorganize both sacred and secular music upon Italian models. This meant that he had to know the best music of every kind; it did not mean that in his own compositions he had to copy any one style slavishly.

Although Schütz learnt from the Italians, he could not be called their disciple. He wrote many sacred motets for voices and instruments combined, as well as an oratorio on the subject of the Resurrection (in German, ‘auferstehunghistorie’, Resurrection story or history). The story is told in free recitative by a single voice just as in Carissimi’s oratorios.

Watch a short documentary on performing Schütz’s ‘Resurrection’ (14 min)

Note that the interviews are in German, but English subtitles are in the video.

Schütz also made experiments in purely secular opera since he produced Peri’s early work ‘Dafne’ at a court performance. He himself wrote an Orpheus on much the same principle. But most important of his works were four settings of the story of the ‘Passion’ according to the four Evangelists, which he wrote late in life.

The Catholic custom of singing the Passion story in Holy Week was one of the parts of the service that England lost at the Reformation and Germany kept, with the difference being that the words were sung in German instead of in Latin.

In the Latin Passions, however, the story and chief characters were intoned in traditional plain-song; only the words of the crowd were set to short dramatic choruses. In the German Passions of Schütz, the words of the story and the conversations are set to free recitatives which are so well joined with the choruses that the whole becomes a complete work of art instead of a patchwork between traditional and original music.

This is a very important difference, for it brought about an entirely new and beautiful kind of church music which would reach its highest point later in the works of J. S. Bach.

It was in the latter part of the 17th century that music became a definite part of the life of every German town of consequence. The organists in the churches and the town musicians became important as composers and performers.

Many members of the Bach family were notable town musicians in the small towns of Thüringen—Erfurt, Arnstadt, and Eisenach—and from them eventually sprang one of the greatest musicians of all time: Johann Sebastian Bach.

Dietrich Buxtehude

Dietrich Buxtehude [pronounced DEE’-ter-ick Books-teh-HOO’-da] was one of the composers who made use of hymn tunes or chorales. He saw that these melodies, besides being the noblest form of congregational church music, could be introduced also into more elaborate forms of composition.

The Chorale Preludes for the organ which Buxtehude and other German composers wrote had a peculiar fitness, for the chorale tunes they based them on belonged to the churches in which they were played. When the organ pieces were heard, they would call to mind theological and Biblical ideas simply by their familiarity. It is a practice that continues to this day in churches.

Listen to Buxtehude’s ‘Prelude 137’ played on the Mascioni organ in Italy (5 min)

Note that the opening of this video is unusual, but the music starts at 0:40.

Buxtehude was particularly energetic in developing church music beyond the limits of the ordinary congregational service. He carried on at Lubeck a kind of sacred concert in the church, called ‘Abendmusik’ (‘evening music’), in which motets and cantatas were sung by a choir with other instruments beside the organ.

Listen to an example of Buxtehude’s ‘Abendmusik’ (2 min)

Buxtehude also wrote some lovely instrumental music for Abendmusik.