Music has been a part of man’s life since God’s creation of the world. When Adam and Eve heard birds singing songs in the garden, they were the first humans to enjoy the beauty of music.

Although there is a long history of music before the Christian church, we will start there because it is the beginning of classical music in the West.

The early Christians sang psalms and hymns to God. Some hymns from the earliest centuries are still sung in a slightly altered form in churches today. Among these are “Veni Creator Spiritus” (Come, Creator Spirit), “Adeste Fideles” (O Come All Ye Faithful) and “Gloria in Excelsis” (Glory in the Highest). As you can tell from the hymn titles, Latin was the universal language of the Christian church.

Nothing is known of music for many centuries outside of the Church. For several hundred years, even the church musicians taught their melodies by ear. Only from about the sixth century onward was there any method of writing music.

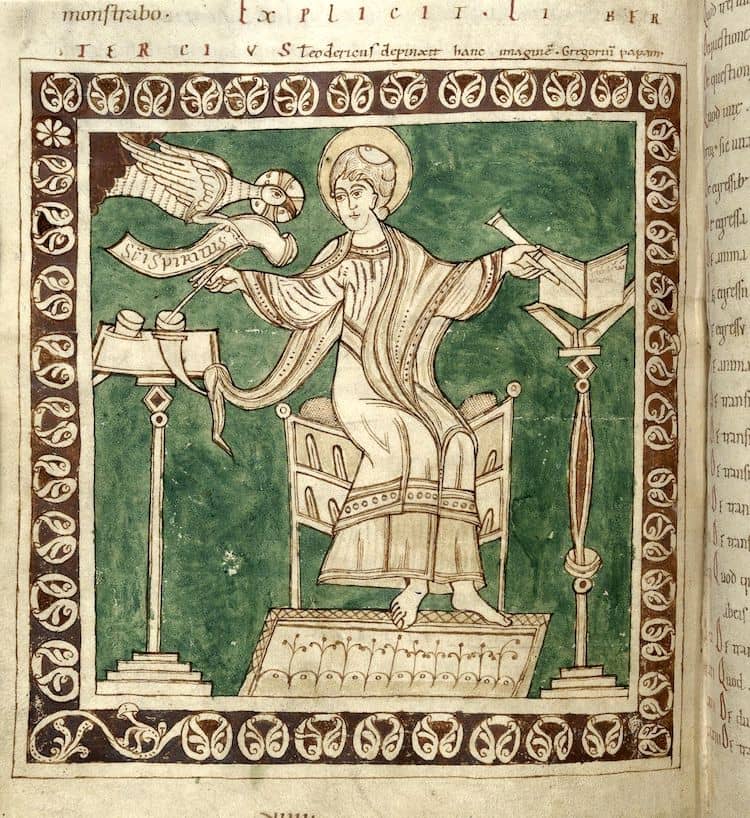

Pope Gregory & Gregorian Chant

In the sixth century, Pope Gregory decided that the melodies of the church must be clearly understood. He believed that all countries which adopted the Christian faith should sing those melodies in the same way. He collected these melodies and had them written down. As a result, they have been known ever since as Gregorian chants.

This type of music is also called homophony, or ‘same sounds in unison’ (homo = same, phono = sound).

We are all familiar with this type of singing since it’s just a single melody that is carried along in a song. In the short piece you’re about to listen to, notice how the same melody is first sung by the man, then is picked up and sung by the women.

Listen to the Gregorian chant “Veni Creator Spiritus” (Come, Holy Spirit) (3 min)

This music is being sung in Latin without instrumental accompaniment.

Gregory gave rules for the composition of church music including the way it should be used in the services. He set up two schools of music in Rome. When his missionaries went into other countries, they did the same there.

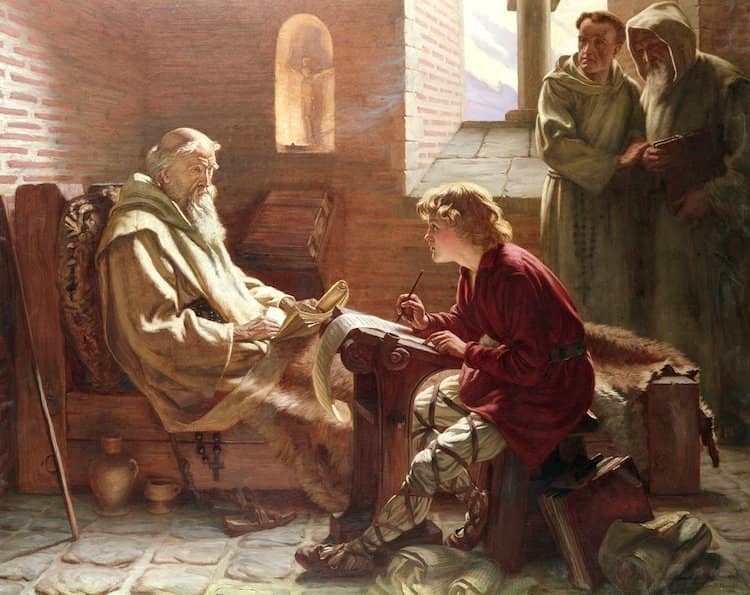

When St. Augustine came to England around 600 BC, he and his followers approached King Ethelbert singing litanies—solemn worship songs that alternate between clergy and attendants. About a hundred years later, a famous school of church music was founded in Northumberland, England. In the reign of Egbert, music and other forms of culture began to flourish among the Saxons. The Venerable Bede, the first English historian, was also a skilled musician.

Early Church Music

When all the people in a church sang together, their voices were not at the same pitch. Pitch defines the location of a tone in relation to others, thus giving it a sense of being high or low. For instance, most men sing at a lower pitch, and most women at a higher pitch.

The idea came of one person singing the same tune at a higher pitch while another voice sang at a lower pitch than the original tune. This was the start of polyphony, or ‘many sounds in unison.’

There were a number of composers who explored different ways of writing polyphony, or polyphonic music. One of them was French composer named Perotin who lived in Paris at beginning of the 13th century. He took the same words but varied the pitch so that it could be sung by four voices (parts grouped by pitch) of singers.

One of his most famous works is entitled “Viderunt Omnes,” which is based on Psalm 98: “All the ends of the earth have seen the prosperity of our God…”

As you listen to the piece sung by a choir below, it is actually a mixture of four different voices sung at four different pitches and merged together. Watch the singers to see the differences.

In comparison to “Veni Creator Spiritus,” notice how different voices sing different tunes at different times, but those tunes weave together into a single piece.

Listen to Perotin’s “Viderunt Omnes” (3 min)

Listen until 3:36 when the choir pauses before starting the next word.

This type of music eventually led to different melodies being sung at the same time. When certain melodies are sung or played together, they form a harmonious whole. The official name for this type of music is called counterpoint. It refers to the art of combining two or more melodies to be performed simultaneously and musically. Counterpoint was the foundation of music for several hundred years.

Counterpoint was first written for voices. Later, the same style was copied for instruments. Therefore, the melodies had to sound good individually as well as together.

Counterpoint gave musicians great pleasure when they discovered the fun of inventing canons and fugues. A canon was a melody sung by one voice followed by each of the others a bar or so later as each in turn began the melody at the same pitch or at a given interval. A round was a very simple canon which began again as soon as it finished.

The earliest known example of English composition was that of a monk, John of Fornsete, who wrote the famous canon “Sumer Is Icumen in.” This has four voices singing the canon while two others keep up a “ground bass,” that is a few notes constantly repeated while the main theme weaves its way above them.

Listen to “Sumer Is Icumen In” (1 min)

To the musical scholars in the monasteries we owe all our knowledge of the music of the time. They wrote about music as they heard it and made it. They found new ways of composing on which all the music which came later was based. To the monks also we largely owe the system of notation which we still use.

In the early days of the church the harp and psaltery were generally used as instruments to accompany the voice. It was told of Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, that

He loved much to hear the harp,

For manne’s wit it maketh sharp.

Next his chamber, by his study,

His harper’s chamber was fast thereby;

Many times, by nights and days,

He had solas of notes and lays.

(From an old poem, written in 1303)

Minstrels

While the Church took care of the theory of music and developed various styles of composition, the people had their own music.

The Latin language, to which all church music had been written, and which was used for all prose and poetry for hundreds of years, gave way at last to the tongues of individual countries. From the south of France (Provence) came that form of French known as the Romance language; from Germany came the Gothic style of German; and the English language was eventually crystallized in the works of Chaucer.

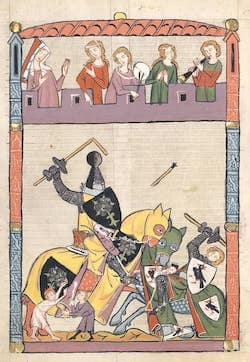

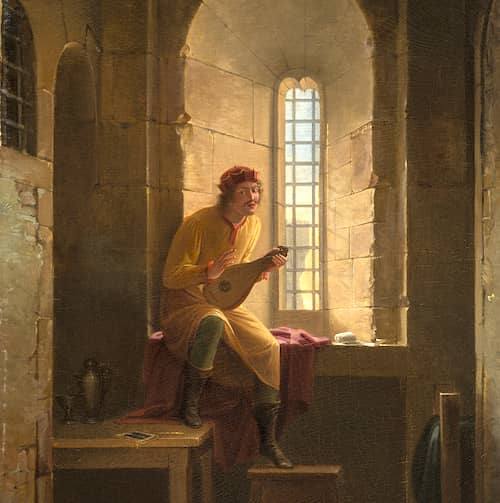

Side by side with these languages grew a secular music. It was created by the professional musicians of the different countries. These were often of high rank and were received as honored guests in the houses of the nobility. They travelled in lordly style, the chief among them having lesser musicians and servants in attendance.

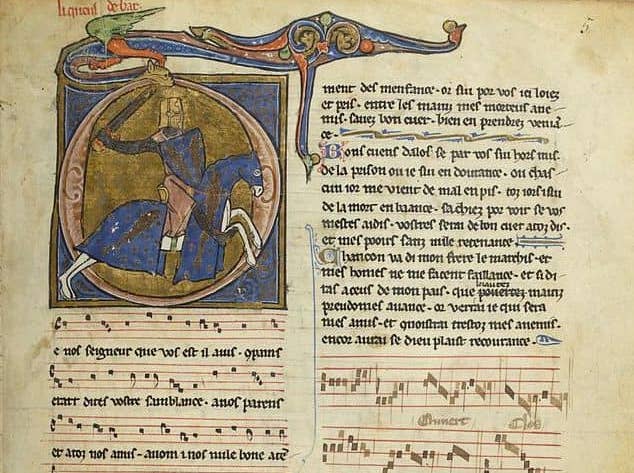

In France

In France, there were the troubadours from Provence and the trouveres from the north. They were attended by jongleurs, the players of instruments who accompanied their songs. The accomplishments of these musicians had to be very varied.

In a book of Advice to Jongleurs, written in 1210, it was stated that a jongleur should be able to play the pipe and tabor, the citole, the symphony, the mandore, the manichord, the seventeen stringed lute, the harp, the gigue, and the ten stringed psaltery.

The troubadours themselves had to be accomplished poets and makers of melody. They travelled from court to court, singing praises not only of brave deeds of chivalry but more especially of the beauty of the ladies of the court.

They entertained the company with stories told to music, and they improvised short songs to suit the mood of the moment. The musicians at any time had to be ready to provide music for dancing. One of the most famous trouveres was Adam de la Hale.

From its earliest days, French poetry has been very clear and definite in form. French musicians took care to make their music fit the words closely; as a result, their tunes took character from the poetry and were written in neat little phrases finished with cadences.

Moreover, songs and dances often went together in France. Plays in which the characters both sang and danced soon became very popular. Among the first of these, and the one from which we will take an example, was a pastoral play by Adam de la Hale called Robin et Marion (Robin and Marion) which was played in 1285.

Listen to ‘Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion’ by Adam de la Hale (1 min)

Just listen to the first minute of this minstrel song to get a feel for the fun and delight it brings.

In Germany

In Germany, there were the guilds of musicians called meistersingers (master singers). Hans Sachs (1494) was the most famous of all these musicians. The theme used by Richard Wagner in his 19th-century opera “Die Meistersinger” is taken from a song of the master singers; in fact, Sachs is one of the chief characters of the opera. Wagner is said to have known their music very well.

Later in Germany, about the thirteenth century, came the minnesingers, of whom the most famous was Walther von der Vogelweide. The lives and music of both mastersingers and minnesingers were much like those of the troubadours.

They seem, however, to have kept a greater independence and their music showed the simple lyric quality of all true German song. Neither did they scorn to sing of the simple things of peasant life.

Listen to the song “Herzeliebes frouwelîn” by Walther von Der Vogelweide (1 min)

Listen to the first minute of this German minnesinger song performed in period dress. He sings of his love for a lady that is not returned.

In England

England from quite an early date had minstrels. Their most popular instrument was some form of harp. Probably this came first from the Celtic harp used by the bards of Wales. The original Welsh harp was called the crwth. Some knowledge of music and minstrelsy was thought necessary to every well-educated person.

The medieval world of instruments and music was quite different from ours. Watch a short video to see how some of the instruments were used; many will look and sound vaguely familiar.

Listen to this Medieval minstrel play on a variety of instruments (3 min)

King Alfred was noted as a minstrel. A story was told of how, when the country was invaded by the Danes, he penetrated the Danish camp by posing as a minstrel. In this way he was able to learn the Danish secrets of attack. When he established the university at Oxford, music was one of the subjects set for study.

King Richard the Lion-hearted was famous as a troubadour. He spent more of his life abroad than in his own country. Blondel was his minstrel, and on one occasion was supposed to have rescued him from prison by means of a song.

One famous minstrel song of England was the “Song of Agincourt” (or “Agincourt Carol”) in praise of Henry V. Henry, however, was a man of action rather than an artist and he discouraged this method of celebrating his deeds.

Listen to “The Agincourt Carol” (1 min)

Listen to the first minute to hear how a medieval song from England would sound.

The Madrigal

Its as the influence of poetry that called musicians to the fact that rhythm is the true basis of their art. However attractive the sound of many voices singing many melodies may be, they must conform to some common standard of rhythm in order to produce an effect of unity.

In the madrigals, the counterpoints became simpler. In the best of them, the length of the musical phrase was regulated by the length and accents of the poetic lines. Often a single note was used to each syllable as in the old songs. Or, if more were used for the sake of expression, they were grouped together into a clear phrase instead of wandering vaguely and holding on a single syllable until the words and sense became unrecognizable.

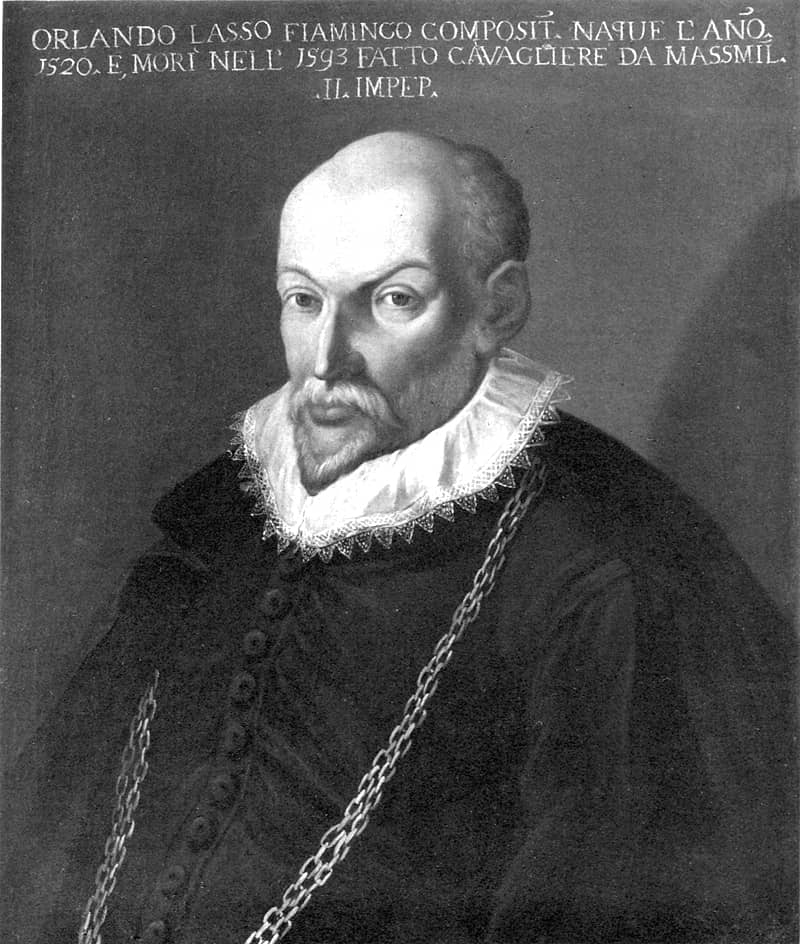

In the work of Orlandus Lassus (1520-94), the greatest of the Franco-Flemish madrigal school, the music became divided into phrases by distinct and beautiful cadences. This has the same effect in music as good punctuation has in literature. If the stops are left out or badly distributed in a book, even the wisest words become nonsense for there is nothing to show where one idea ends and another begins.

Similarly, the division of musical sentences is shown by the use of certain chords which make an ending and separate one idea from another. These are called cadences.

Both in his madrigals and in his church works, Lassus used the same means for giving order and clearness to his ideas. In his church music, he was not so bound by the rhythm of words as he was in his settings of secular poetry.

In his Penitential Psalms, Lassus had great and deep feelings to express. He naturally thought more of melodic beauty as well making the voices join in rich and varied harmony. Even in these, however, the rhythmic form is not disregarded as it was in the church music written before the rise of the Madrigal.

This opening of a graceful little French song by Lassus shows how closely he could make his music follow the meter of words. Notice the cadences at the ends of the lines. Also, note the fact that although the counterpoint is very simple, each voice moves quite freely at the French words ‘et prend’ (pronounced ‘eh prawn’) without destroying the rhythm of the verse.